Pinus resinosa, Red Pine

Red pine, Pinus resinosa, is a fairly common tree in our area. It typically reaches sixty to seventy feet in height with a trunk diameter of a foot or more. The bark has a reddish cast and consists of thick, scaly plates. The cones are small and egg-shaped. The two dark-green needles in each fascicle (bundle) are three to six inches long and they form in clusters at the ends of branches.

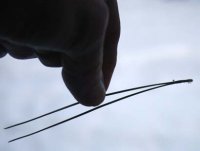

Pinus resinosa prefers dry, sandy soils although it can do well in many soils provided there is adequate drainage. In North America it is found principally in the Great Lakes area and eastern Canada. In New York state, it grows wild in the higher elevations- typically the Adirondacks and Catskills. In our region it grows wild in the driest, steepest, most exposed south- and west-facing slopes. Northern Pennsylvania is the southern extent of its range. It germinates best on fire-cleared areas and its thick bark affords it a level of protection against fire. Although less common, the imported Austrian pine (Pinus nigra) can often be found growing along with our own red pines. This European native resembles P. resinosa and was similarly planted in our area years ago for its timber value and fast growth. As the Latin name suggests, Austrian pine is also called "black pine". Red pine, on the other hand, is also known as "Norway pine". It is indigenous to North America, not Norway, but may have gotten this common name due to confusion with Norway spruce by our original English colonists. The way to tell them apart is to take a leaf (needle) and bend it in half. If it snaps in two it is a red pine; if it flexes without breaking it is the Austrian pine. For years I could never remember which was which so I came up with a mnemonic: "If you snap your fingers they will eventually turn red." Austrian pine leaves are usually a little longer than red pine, too. I found it interesting that the Cornell Handbook of Nature Study (ref. 1) and Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets (ref. 2), published in 1920 and 1904, respectively, do not mention red pine at all, although they both discuss Austrian pines in our area. The majority of the red pines we encounter in our area are cultivated. Landowners often plant them due to their fast growth, aesthetic value and relative immunity from disease. Large numbers were planted in the 1920's and 1930's on abandoned farmland to control erosion and as a potential source of timber (ref 3). They often didn't do well and died where the soils were too wet. These straight rows of pines are ecologically poor. Such monocultural areas "are often biological deserts, which host little except pine diseases and pine insect foragers." (ref 4)References cited:

1. Comstock, Anna Botsford, Cornell Handbook of Nature-Study, Comstock Publishing Company, Ithaca, NY, 1920

2. Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets, State of New York Department of Agriculture, Albany, NY, 1904, p338-339

3. Tobiessen, Peter and Werner, Mary B., "Hardwood seedling survival under plantations of Scotch Pine and Red Pine in central New York", Ecology, 61(1), 1980, pp25-29

4. Eastman, John, The Book of Forest and Thicket, Stackpole Books, 1992, p160-163.

Other references:

5. Cope, J.A. and Winch, Fred E. Jr., Know your Trees, Cornell Cooperative Extension Booklet, 1998

6. National Audubon Society, Field Guide to the Trees/Eastern Region, Alfred Knopf Inc., 1980

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke