Joe O'Rourke

'Joe-Pye weed'. It's the common name given to several species of the genus Eutrochium. Many of us know these flowers as members of the genus Eupatorium. Just last year, based on chloroplast DNA analysis, it was proposed that Eupatoriadelphus should be treated as a distinct genus and that the earlier name, Eutrochium, be applied to the Joe-Pye weeds.

Joe-Pye weed is a member of the aster family, Asteraceae. In this area of central New York State, four species can be found: E. dubium (Joe-Pye thoroughwort), E. fistulosum (hollow Joe-Pye weed), E. maculatum (spotted Joe-Pye weed), and E. purpureum (sweetscented Joe-Pye weed). This article will focus on the more common one in our area, E. maculatum var. maculatum, spotted Joe-Pye weed.

Eutrochium maculatum likes wet soil conditions and is a common sight in our calcareous fens, wet meadows and thickets. Besides reproducing by seeds, this perennial herb spreads by rhizomes and is sometimes found in large colonies.

The stem often has dark purple specks, from which it derives part of its common name, although it may be solid purple. The other part of its name is said to derive from a Native American doctor who used the plant to cure fevers in colonial times. The stem is pubescent, not glaucous. Most eye-catching are the four (sometimes three) or five whorled leaves surrounding the stem. The leaves are coarsely dentate, lanceolate, and 2 1/2-8" long.The flowers are borne in flat-topped inflorescences, 4 to 5 1/2" wide. The fuzzy pinkish-purple clusters, consisting entirely of disk flowers, are frequented by nectar-seeking insects such as butterflies, bees, dragonflies and wasps. Under the right conditions, the plant can grow to a height of seven feet. The plants emerge in early June, but do not begin flowering until mid-July. They reach their peak in mid August.

The entire plant is known historically as an alternative medicinal for various purposes. The leaves, when crushed, have an apple smell and, when burned, are said to repel flies. A concoction made of the tea from the roots or flowers can reputedly cause sweating and was used by the early settlers to break fevers. Our native white-tailed deer and eastern cottontail will feed on the whole plant and turkeys, mallards and the white-footed mouse will eat the seeds.The flowers are attractive and are usually carried in nurseries for they make appealing garden plants. The bud clusters are colorful, even before opening, and they are long-blooming afterward. Because they are heavy pollen-bearers, perhaps their greatest commercial appeal is their ability to attract large, showy butterflies like swallowtails and monarchs.

For additional photos, click on the plant name in the box on the right.

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

Status & Range

The American hart’s tongue fern is state and federally listed as threatened, globally imperiled, and generally rare and very patchy throughout its range. It is currently known from two counties in NY, but ranges into New Brunswick, the Bruce Peninsula of Ontario, and Upper Michigan, with two disjunct populations in cool sinkholes and caves of Tennessee and Alabama. According to Don Leopold, the first discovery of this species in North America was at a central NY site in 1807, and the NY sites represent 9% of the US populations (Ref. 4). The European plants are much more wide-ranging both ecologically and geographically, and are relatively speaking, common, whereas the North American plants are very rare and local. As described below, this more exacting nature extends to its suitability to cultivation.

Appearance

Hart’s tongue fern is quite distinctive when seen outside of a garden (where anything goes). The easy way to remember the look of this fern is given by Wikipedia. "The tongue-shaped leaves have given rise to the common name ‘Hart's tongue fern’. The sori pattern is reminiscent of a centipede's legs, and scolopendrium is Latin for ‘centipede’."

Hart’s tongue fern is quite distinctive when seen outside of a garden (where anything goes). The easy way to remember the look of this fern is given by Wikipedia. "The tongue-shaped leaves have given rise to the common name ‘Hart's tongue fern’. The sori pattern is reminiscent of a centipede's legs, and scolopendrium is Latin for ‘centipede’."

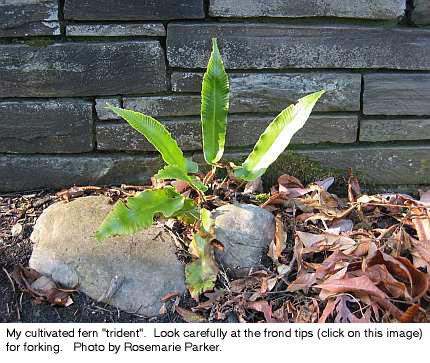

Long strap-like fronds are 6-8" long (up to 16" for European variety) and 1-2" wide (European variety is generally wider than the American variety). The frond is glossy, bright green, somewhat leathery, and the margin is entire. The frond tip can be pointed or blunt (more pointy in the American variety), the veins fork, and the base is chordate. The stalk (rachis) is brownish and glabrous, with lanceolate scales (again more pointy in the American variety). The sori are linear and perpendicular to the rachis; the American variety is likely to have sori only on the upper two-thirds or half of the blade, while the European variety MAY be more completely covered. Some individuals in the wild North American populations may have been modified by genetic contact with each other and/or European varieties, either accidentally or via misguided, albeit well-intentioned, efforts to "save" the plants by transplants and spore releases (Ref. 5). Thus some NY specimens may have some aspects of the European variety. (Ref. 6)

Habitat

The European variety is common in England, France and Germany, where it can be found on limestone walls of old churches & gardens and in calcareous ravines. It can also be found in scattered locations elsewhere in Europe. The American variety shows a similar preference for neutral to limy soil, rocks, and high humidity. American hart’s tongue fern is found on wet limestone cliffs, cave entrances, and outcrops (Ref. 1). In New York they are generally found on north-facing slopes (mid-slope position) under deciduous canopy or in glacial plunge basins and narrow meltwater channels with high humidity (Ref. 4).

Cultivation

Although earlier texts state that both American and European varieties can be grown "if natural conditions are simulated" (Ref. 3), more recent texts strongly differ. To start with, several references note that part of the reason for the scarcity of the North American variety is due to plant collectors. William Cullina summarizes the experience of the New England Wildflower Society’s Garden in the Woods this way: Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum has a "well-deserved reputation that is far less amiable [than the European variety]" ... [It has] proven recalcitrant in cultivation and quickly perishes even under expert care ... [As a] rare species, even spore collection is discouraged ... (Ref. 1)."

Although earlier texts state that both American and European varieties can be grown "if natural conditions are simulated" (Ref. 3), more recent texts strongly differ. To start with, several references note that part of the reason for the scarcity of the North American variety is due to plant collectors. William Cullina summarizes the experience of the New England Wildflower Society’s Garden in the Woods this way: Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum has a "well-deserved reputation that is far less amiable [than the European variety]" ... [It has] proven recalcitrant in cultivation and quickly perishes even under expert care ... [As a] rare species, even spore collection is discouraged ... (Ref. 1)."

And why would you want to? A rare species which dies on the experts? The Garden in the Woods opted to grow the European variety as a substitute. The European variety grows very well in gardens and provides all the visual benefits of the native one. It can be started easily from spores and transplants well. This time, ethics, morality, and practicality all lead to the same conclusion. If you are so lucky as to see a wild hart’s tongue fern in the North American woods, leave every bit of it there. Take pictures. Wish it well. Don’t reveal the location!

References

1. Cullina, William, New England Wildflower Society, Native Ferns, Moss & Grasses, Frances Tenenbaum, 2008, p36-37.

2. EFloras: Flora of North America Vol. 2

3. Foster, F. Gordon, Ferns to Know & Grow, 2nd revised ed., Hawthorne Books, 1976, p152-153.

4. Leopold, Donald J., Native Plants of the Northeast, Timber Press, 2005, p40.

5. Nature Serve - Version 7.1 (2 February 2009), Data last updated: July 17, 2009 Nature Serve

6. Weldy, Troy and David Werier. 2009 New York Flora Atlas. [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (original application development), Florida Center for Community Design and Research. University of South Florida]. New York Flora Association, Albany, New York. 2009 New York Flora Atlas

7. Wikipedia: Wikipedia

About

By Rosemarie Parker

Photos by Joe O'Rourke, Rosemarie Parker

Plants Referenced

Summer time for me is the season for fresh local fruit and ... wildflowers! Since this is a group devoted to the study of our local flora, I am confident that there are others who share my excitement about taking a hike to a new section of the woods in the cool of the morning hours and discovering yet another new wildflower. I get a sense of satisfaction from making a new notation in my Newcomb’s for that new wildflower sighting.

Lately, I have taken on the task of identifying butterflies in our area - great spangled fritillaries, little wood satyrs, orange sulfurs, etc. Unlike wildflowers, the challenge with identifying butterflies is that they just won’t stay still for this curious naturalist, which usually results in a chase. Anyway, wildflowers, especially ones in sunny areas, are generally aflutter with butterflies, each busily probing its host plant with its proboscis, or mouthpart, seeking nectar. So, to fully appreciate our wildflowers, it is prudent to learn who their pollinators are. Butterflies are among the many flying insects that happily take on this job.One of the host plants which several of our local butterfly species depend upon is Spreading Dogbane, Apocynum androsaemifolium. Here in the Finger Lakes region, it blooms from late June to early August. This common native is a shrubby wildflower which grows to a height of 2-4 feet. It can be locally abundant, growing in colonies, and in sunny, dry areas such as roadsides, sandy areas, old fields and disturbed places. The delicate, light pink blossoms are about ¼", bell-shaped, and form in loose clusters on the ends of branches. The leaves are oval with a rounded point, alternate, entire, hairy beneath, and up to 4" long. Its distinct reddish stems lack a defined central stalk. The fruit are long, slender, and pointed pods, found hanging in pairs. (Ladd, 2001)

Dogbane is an old-fashioned term, referring to the fact that it was once used to treat a dog bite. “The only apparent connection between the American plant and dogs was its occasional use to treat people bitten by mad dogs.” (Sanders, 2003) However, “... they are certainly the bane of flies and various other smaller insects for whom they are a deathtrap.” (Sanders, 2003) Other insects with shorter mouthparts become mercilessly stuck in the flower’s interior area, which is barbed. These unwelcome pollen poachers are hopelessly trapped and die. It is common to see these dead insects dangling by their tongues from the flower. (Sanders, 2003)

Typical of dogbanes, the latex-like sap is poisonous and acts like a deterrent to most animals. It is mildly toxic to humans. When exposed to air, the white sap will dry into a soft rubbery substance. Since the leaves have an intensely acrid taste, this plant was once called bitterroot. (Sanders, 2003)

By design, dogbane flowers are adapted to attract butterflies, upon which the wildflower is dependent as a pollinator. A butterflies, such as a monarch, dips its proboscis into the blossom to collect the sweet nectar therein. The nectar serves as an attractant to lure the butterfly into the pollen-bearing region of the flower. (Sanders, 2003) The pollen brushes off onto the legs and other body parts of the pollinator, which is then transported to neighboring plants of the same species for fertilization, ensuring genetic variety. While this plant maybe poisonous to most mammals, it is highly attractive to butterflies and other insects. Even though school children are taught that milkweed is their only food, spreading dogbane is also the monarch butterfly’s host plant. They will feed on the leaves and make their chrysalises on the undersides of the leaves. [See editor's note, below.] Like monarchs and milkweeds, the toxins found in the latex sap of the dogbane provide a natural chemical defense against predators once it has been ingested by the butterfly larvae. (Sanders, 2003) Other butterflies, such as the Canadian tiger swallowtail, cabbage whites, hairstreaks, fritillaries, checker spots, and red admiral, also feed upon spreading dogbane. (Weber, 2002)

Should a colony of dogbane be located near an open hilltop, one may find numerous butterflies clustered at the top, in a behavior known as ‘hilltopping’. This involves mainly the males, actively cruising the singles scene, who congregate at the highest point of the surrounding landscape looking for a mate. Due to the butterfly’s limited distance vision and the fact that its host plants are naturally widely disbursed, hill tops serve as a singles bar. Since males are very territorial, early arrivals choose the most strategic spots to patrol, which is heartily defended, and chasing away rivals is all part of the action. The chances of successfully finding a mate increase significantly if everyone congregates in one area. A female will take a break from seeking a host plant upon which to lay her eggs long enough to fly uphill and mate. It is found that different species of butterflies dominate a hilltop at different times of the day, perhaps as a way of avoiding the distraction of other types of butterflies also seeking mates. Other insects, such as wasps and bees, also use this 'hilltopping' strategy. (Williams, 2005)

Another courtship behavior, ascending flight, occurs when a female is uninterested in the advances of an amorous male. This uninterested female signals that she is unready to mate by flying upwards; the male pursues. The resulting upward spiraling flight occurs when the male pursues the female, but does not take the hint that she is unready to mate. The same instinctive flight pattern occurs between rival males while defending their territories during intense mating activity. (Williams, 2005)

Butterflies gain needed sodium and other nutrients by eating soil and drinking from muddy puddles. In a behavior known as ‘puddling’, male butterflies will congregate at puddles and form ‘puddle clubs’. “It has been shown ... that the sodium accumulated during puddling is passed on, along with sperm, to a female at mating in a nuptial gift he helps by providing nutrients.” (Williams, 2005) These extra nutrients are used by the female for egg production. “Tiger swallowtails are notorious puddlers.” (Weber, 2002) Other sources of sodium are “carrion, animal excrement, sweat-soaked clothing, campfires, and urinals.” (Williams, 2005) So, while puddle clubs are stag parties for males, they also enable the male to contribute to reproduction in a more passive manner. (Williams, 2005)Other behaviors include nectaring (when the adults feed on nectar, their primary food) and basking, which is when they warm themselves up by “spread[ing] their wings in sunny sites and act[ing] like small solar panels to collect heat.” (Weber, 2002)

Next time you are out hunting for that elusive wildflower, take the time to see who is fluttering in the neighborhood. Remember, wildflowers do not occur in isolation, but are part of a larger interconnecting ecosystem, in which they form a vital link. Without butterflies, there would be no spreading dogbane, and vice versa.

Sources:

Sanders, J. 2003. The Secrets of Wildflowers. Lyons Press, Guilford, CT

Ladd, D. 2001. North Woods Wildflowers. Falcon Publishing, Helena, MT

Weber, L. 2002. Butterflies of New England. Kollath-Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN

Williams, E. 2005. The Nature Handbook. Oxford University Press, NY, NY

Editor's note Jan. 2014. Following up on a reader's question suggests that references to monarchs utilizing Apocynum may be a case of repeated references to an original, erroneous report. Robert Dirig, Cornell, states the following:

- "Here's a quote from a long essay on the Monarch that I wrote a few years ago:

- Confined N.Y. females refused to oviposit on Spreading Dogbane (Apocynum androsaemifolium, Apocynaceae), nor would larvae eat it. Literature reports of this plant as a Monarch larval host may be misidentifications, since dogbanes also contain milky latex and superficially resemble slender milkweeds.

- I have never found a wild larva on either Spreading Dogbane or Indian Hemp. Female Monarchs also would not lay eggs on local Vincetoxicum/Cynanchum species, and larvae wouldn't eat them. In the Northeast, they seem to be confined to milkweed hosts (Asclepias)."

About

By Melanie Kozlowski

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

The flowers are generally white but sometimes have a pink tint. They are funnel-shaped and can reach 3" in length. The leaves are large, triangular in shape and have pointed tips.

Although native to our area, their aggressive growth habit makes them somewhat of a nuisance. They can reach ten feet in height and smother the plants they are growing on. Their huge network of creeping rhizomes, plus a taproot that can be up to ten feet in length, can make them very difficult to remove. They are also allelopathic, releasing toxins into the soil that inhibit or retard plant growth.Hedge Bindweed is often confused with another common wild morning-glory, Field Bindweed, or Convolvulus arvensis. Field Bindweed is non-native, has smaller flowers and leaves, and prefers more open areas. It is easily differentiated from our native species by inspecting the leaves. In C. sepium, the base of the leaf has two points, or 'dog ears,' whereas the base of a C. arvensis leaf comes to a single point.

In the 60's, it was a fad to crush the seeds of the popular garden variety "Heavenly Blue" morning glory and consume them. In small quantities the seeds produced hallucinations. In large quantities they were poisonous. The seeds of our native morning-glory have the same hallucinogenic effect.C. sepium blooms in our area from June to September.

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke