Joe O'Rourke

Gaywings (Polygala paucifolia) is one of our more curious-looking local wildflowers. It emerges from the forest floor in the month of May. This low growing plant of dry, rich woods, has unusual orchid-like flowers, and is known by several common names including flowering wintergreen and fringed polygala. The blossoms are pink to rose-purple in color, about 1-1.7 cm long, and usually found growing singly in the axils of the upper leaves. When in full bloom, two prominent petals flare out from the corolla, framing a whimsically fringed petal at the center.

Gaywings is not an orchid but is actually one of over 60 members of the genus Polygala that occur in the US. Polygalas make up a large part of the Milkwort family (Polygalaceae), the name stemming from the Greek for ‘much’ (poly) and ‘milk’ (gala). This is because eating milkworts was believed to increase lactation in mammals such as cows and even humans. Other Polygala species that occur in the northeast include the short-leaved and cross-leaved milkworts (P. brevifolia and P. cruciata) and one rare orange variety, P. lutea. Generally, these others are easily distinguishable from gaywings, having much smaller flowers that occur in spikes or racemes.Like many spring wildflowers in the temperate zone, most Polygala species rely on ants to disperse their seeds, a strategy called myrmecochory. Polygala seeds have nutrient-rich attachments called elaiosomes that attract ants, which then drag the seeds into their nests. Ants feed the elaiosomes to their young, leaving the detached seed to germinate underground, far from the parent plant. Scientists have determined that the elaiosome evolved in this plant group about 55 million years ago and that this allowed the evolution of many new, specialized species of Polygala. This was well before the diversification of ants themselves, so it is most likely that the elaiosome originally had some other function before it was co-opted as a bribe for seed dispersal services!

Gaywings is an endangered species in Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio, but it is secure throughout the rest of its range from central and eastern Canada down the east coast to Georgia. Herbarium records from the Bailey Hortorium and New York Botanical Garden historically place this species in Tompkins County at locations such as Ellis Hollow Swamp, along Six-mile Creek, and in parts of Danby. In more recent years FLNPS members have spotted this charming wildflower at Buttermilk Falls and at Beaver Lake Nature Center, north of Syracuse where you might be able to catch a glimpse of it this year.References:

Forest, et al. (2007) The role of biotic and abiotic factors in evolution of ant dispersal in the Milkwort family (Polygalaceae). Evolution, 61:7:1675-1694

USDA Plants Database

The Polygalaceae Website (this site has links which do not seem to function well, but the information on the site itself is probably fine - Ed. 2012)

Lakehead University Faculty of Forestry and the Forest Environment

US Forest Service (This has a good description of the flower, see paragraph 2. - Ed. 2012)

About

By Billie Gould

Photos by Joe O'Rourke, USDA Plants

Plants Referenced

Red pine, Pinus resinosa, is a fairly common tree in our area. It typically reaches sixty to seventy feet in height with a trunk diameter of a foot or more. The bark has a reddish cast and consists of thick, scaly plates. The cones are small and egg-shaped. The two dark-green needles in each fascicle (bundle) are three to six inches long and they form in clusters at the ends of branches.

Pinus resinosa prefers dry, sandy soils although it can do well in many soils provided there is adequate drainage. In North America it is found principally in the Great Lakes area and eastern Canada. In New York state, it grows wild in the higher elevations- typically the Adirondacks and Catskills. In our region it grows wild in the driest, steepest, most exposed south- and west-facing slopes. Northern Pennsylvania is the southern extent of its range. It germinates best on fire-cleared areas and its thick bark affords it a level of protection against fire. Although less common, the imported Austrian pine (Pinus nigra) can often be found growing along with our own red pines. This European native resembles P. resinosa and was similarly planted in our area years ago for its timber value and fast growth. As the Latin name suggests, Austrian pine is also called "black pine". Red pine, on the other hand, is also known as "Norway pine". It is indigenous to North America, not Norway, but may have gotten this common name due to confusion with Norway spruce by our original English colonists. The way to tell them apart is to take a leaf (needle) and bend it in half. If it snaps in two it is a red pine; if it flexes without breaking it is the Austrian pine. For years I could never remember which was which so I came up with a mnemonic: "If you snap your fingers they will eventually turn red." Austrian pine leaves are usually a little longer than red pine, too. I found it interesting that the Cornell Handbook of Nature Study (ref. 1) and Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets (ref. 2), published in 1920 and 1904, respectively, do not mention red pine at all, although they both discuss Austrian pines in our area. The majority of the red pines we encounter in our area are cultivated. Landowners often plant them due to their fast growth, aesthetic value and relative immunity from disease. Large numbers were planted in the 1920's and 1930's on abandoned farmland to control erosion and as a potential source of timber (ref 3). They often didn't do well and died where the soils were too wet. These straight rows of pines are ecologically poor. Such monocultural areas "are often biological deserts, which host little except pine diseases and pine insect foragers." (ref 4)References cited:

1. Comstock, Anna Botsford, Cornell Handbook of Nature-Study, Comstock Publishing Company, Ithaca, NY, 1920

2. Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets, State of New York Department of Agriculture, Albany, NY, 1904, p338-339

3. Tobiessen, Peter and Werner, Mary B., "Hardwood seedling survival under plantations of Scotch Pine and Red Pine in central New York", Ecology, 61(1), 1980, pp25-29

4. Eastman, John, The Book of Forest and Thicket, Stackpole Books, 1992, p160-163.

Other references:

5. Cope, J.A. and Winch, Fred E. Jr., Know your Trees, Cornell Cooperative Extension Booklet, 1998

6. National Audubon Society, Field Guide to the Trees/Eastern Region, Alfred Knopf Inc., 1980

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

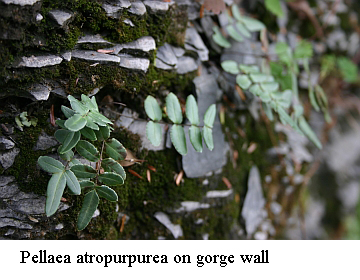

Pellaea atropurpurea - From the Greek pellos, dusky, describing the bluish-gray coloring of the leaves and atro (dark) plus purpurea (purple).(Stuart 2008)

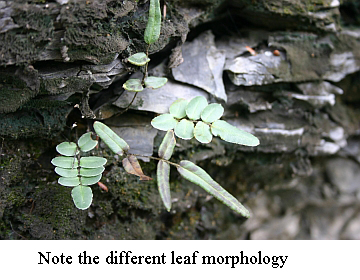

During a recent trip to a Lansing gorge, I was introduced to an interesting evergreen fern, Pellaea atropurpurea (purple cliff brake). It is fairly small, and does not attract attention like a large clump of Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) or marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis), two of our region's common evergreen ferns. But it is one of those gems that forcibly reminds me to appreciate one of the Finger Lakes' characteristic habitats - lime outcrops and exposed shale in gorge walls - for those are the favored habitats of this little fern. Although purple cliff brake is native to a very wide region (Guatemala to southern New England & Canada to Florida), the descriptions of where it is found within its native range are all a variation on "dry, limestone rich cliffs and outcroppings". I gather that purple cliff brake can grow under other conditions, but is most common on these dry, limey situations or in the soil immediately adjacent to outcrops. This is particularly interesting to me, since the specimens I saw were just above the high water line in the gorge, along with some rather robust mosses. I would guess that the area is moist at least part of the year, although it probably bakes in the summer.Identification: Pellaea atropurpurea is fairly distinctive, particularly if you look during the time of year when deciduous ferns are browning or absent. The overall look is an asymmetric clump; the leaves are growing from a rhizome and are slightly dimorphic, i.e. the fertile fronds are longer and more divided than the sterile fronds. The stipe (leaf stalk) is thin, wiry, and hairy, especially on the upper surface and colored dark purple or black. Although the fern is often described with blades from 2 inches to a bit over a foot long, the ones we saw were on the short side. According to the Flora of North America, some P. atropurpurea populations have hybridized with other Pellaea species. Luckily for Finger Lakes plant lovers, these are found west of our region.

More specific ID:Blade: usually 2-pinnate at the base, but sometimes only once pinnate, elongate-deltate to lanceolate, leathery, rachis hairy, sparsely villous below near midrib of ultimate segments.

Pinnae: 5 to 11 pairs, bluish-green, lower pinnae stalked, upper sessile, terminal pinnae like the upper lateral ones; pinnae perpendicular to rachis or ascending, not decurrent on rachis; pinnules (leafules) sessile or nearly so; veins obscure; margins weakly recurved to plane on fertile segments. Spores are clustered at the edges of the pinnules.

Pellaea glabella, the smooth cliff brake, is similar to P. atropurpurea, but differing in its monomorphic leaves, smaller size, and particularly the glabrous stipe and rachis. (The key point is that the wiry stalk in the middle of the frond is not hairy like the purple cliff brake.) Pellaea glabella is not nearly as common as the purple cliff brake in the Finger Lakes region, in fact P. glabella is threatened in New York (Weldy and Werier 2008). But you might find some.

Status: Pellaea atropurpurea is protected in New York State as "exploitably vulnerable", a status given to species which have sufficient population so long as collecting is prevented. Pellaea atropurpurea is endangered in Florida, Iowa & Rhode Island, and threatened in Michigan. (USDA Plants).

Growing and Propagating: The purple cliff brake grows in full to nearly full sun in dry limey conditions. It can be propagated by spores, which ripen June-September. Rock gardeners with crevice beds can provide the correct conditions (Goroff 2001), but most of us will have the fun of scrambling over the rocks to see it in a natural habitat. So, next time you find yourself next to a shale cliff, look even closer.

References: Note that the identification section above is a composite of all of these sources.

Connecticut Botanical Society; 2008

Flora of North America; 2008; Volume 2

Goroff, Iza; 2001; "Plant of the Month"; North American Rock Garden Society (2012: no longer on web site but in lots of new places)

Missouri Botanical Garden (Dan Tenaglia), 2008

Stuart, Tom; Hardy Fern Library; 2008

U. S. Department of Agriculture Plants Database ; 2008

Weldy, Troy and David Werier. 2008; New York Flora Atlas.

About

By Rosemarie Parker

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

Photograph of fruit copyright Thomas H. Kent from Florafinder.com (Creative Commons license)

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke, Thomas H. Kent

Plants Referenced

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

The common name refers to its paired leaflets that resemble butterfly wings, both open and shut. The Latin name was bestowed by the famous botanist Benjamin Smith Barton to honor Thomas Jefferson, at a meeting of the American Philosophical Society on May 18, 1792 - a meeting that Jefferson did not attend.

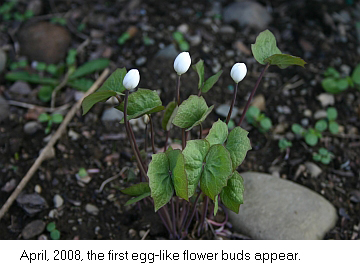

Like many of our spring ephemerals, twinleaf seeds need multiple periods of alternating cold and warm periods before they will germinate. This requirement, called stratification, is carried out by nature to ensure that our early wildflowers do not germinate prematurely during that first warm spell in April when a later May frost may kill the young seedlings. If the seeds are not fresh enough, they may not grow. Once germinated, however, twinleaf will readily thrive and spread in rich soil with a shady habitat. They naturally like rich, deciduous woods, but mine is in a small garden bordering my back deck where it only receives the morning sun. If you'd like to see this plant in bloom, perhaps the best place to visit is the Mundy Wildflower Garden at Cornell Plantations. It flowers there beginning in mid-April. Better yet, purchase some seeds or plants and plant them in your own garden where you'll have your own welcomer of flowers to come.About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

Early in September, 1998, I had the pleasure of seeing three of our native gentians, Gentiana clausa, Gentianella quinquefolia, and Gentianopsis crinita. I did this as a participant in one of the summer plant walks sponsored by the Finger Lakes Native Plant Society, led by David Nakita Werier.

We started our walk in the Connecticut Hill area and found Gentianella quinquefolia (stiff gentian or ague-weed) after a few minutes of searching, on the margins of a gravely road turn-around. This gentian is listed in Rare and Scarce Vascular Plants of the Cayuga Lake Basin (by Robert Wesley) as “scarce”, which means there are six to twenty known occurrences. It is a pretty little thing: an annual or sometimes biennial. The specimens that we saw were all shorter than typical, perhaps because they had been mowed earlier in the season by a road crew. Nonetheless, they were in full flower. Gentianella quinquefolia has exquisite small flowers in many terminal clusters of three to five. When viewed from above, it looks like a handful of 15 or 20 small amethyst gems. These flowers were generally closed, although they do open up in the sun when mature. After finding it in this spot, we walked back down the road and found it in a dozen more places, always on the side of the road ditch, where the soil looked heavy but full of gravel. I should mention that this was a wooded area; the only sun exposure was the road and road margins.Our next find was half a county away in Shindagin Hollow, where Gentiana clausa was growing on the side of the ditch. It was competing with other rampant growth and was about 2.5 feet tall. Gentiana clausa, also listed as scarce by Wesley, is called the closed or bottle gentian, for the simple reason that the flowers never open up. They are borne in terminal and sub-terminal clusters. I have to admit that I have a soft spot for this gentian, because for many years it has grown happily in my garden in Allegany County, in extremely heavy clay soil. It is stunning in bloom and even makes an excellent cut flower. It gets a wonderful reddish cast on the foliage as the weather turns frosty.

Gentiana clausa is often confused with G. andrewsii. In fact, I always thought the gentian that I grew was G. andrewsii. To tell the difference, you take a blossom, slit it lengthwise and open it out flat. On G. clausa the plicae that are between the segments of the corolla are divided into 2 or 3 segments and are not fringed. On G. andrewsii they are fringed.

Our last gentian was one that I have always wanted to see: Gentianopsis crinita, the fringed gentian. This gem was very impressive. We could have gotten a perfectly good look at it without getting out of our cars. Out of respect, we did disembark, and took our life in our hands as we huddled on the narrow shoulder of the road, peered down into a wet ditch, and then gazed up a bank so steep that only one of our group ventured up it. He reported that the gentian grew not only in the ditch, but also quite a way up this bank. This site was sunny, but since there was water running in the ditch, I suspect that even the soil up the hill might have been moist. Gentianopsis crinita is a biennial, with single terminal flowers that were larger than I had imagined. Each stunningly blue flower was about two inches long, with heavily fringed petals. Although on this site it was obviously thriving, it is listed as “rare”, which is two to five occurrences on Wesley’s list.When I got home from this “walk”, which I renamed a “drive”, I was tired—of driving—but thrilled to have seen these three plants in their native habitats.

This article was originally written for and published in The Green Dragon, newsletter of the Adirondack Chapter of the North American Rock Garden Society.

Additional images added:

G. clausa - Mt. Cuba Center - http://www.mtcubacenter.org/plant-finder/details/gentiana-clausa/

G. quinquefolia - Rob Baller, courtesy of Fred Burwell in a lovely ramble about Wisconsin wildflowers http://fredburwell.com/tag/wildflowers/

About

By Anne Klingensmith

Photos by Joe O'Rourke, Rob Baller, Mt. Cuba Center

Plants Referenced

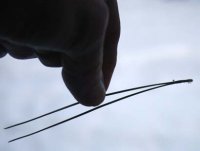

Drosera rotundifolia, the round-leaved sundew, is one of several insectivorous plants that live in our area. It is the more common of our two native sundews, the other being D. intermedia, the spatulate-leaved sundew. As the common names indicate, the leaves of D. rotundifolia are round while those of D. intermedia are more oval, or spoon-shaped. Both belong to the family Droseraceae.

Although D. rotundifolia is common in our area, many have never seen it. It is a tiny plant whose leaves are only 1/2" long and it often grows mixed in with sphagnum moss. When enough plants congregate, the bright red color often reveals its presence. I've seen it in bogs, on hummocks in fens and growing in a wet area right along the side of Route 11 in Tully, NY. Drosera intermedia is much more scare. I've only seen it once in a bog near Whitney Point. Both of these species are protected plants in New York State, classified as EV (Exploitably Vulnerable).The sundews thrive in environments where other plants cannot compete. Under conditions that lack the nitrogen and phosphorous that plants need, or low PH that prevents plants from utilizing the available nutrients, sundews compensate by capturing insects and obtaining the needed nutrients directly from the insect bodies.

The plant morphology efficiently supports this lifestyle. The leaves form a rosette which lies nearly on the ground, exposing its upper leaf surface. The surface is covered with red tentacle-like hairs that exude a sticky, sweet, substance that attracts insects. When an insect lands on a leaf, the mucilage helps to hold the insect while the leaf secretes proteolytic enzymes that digest the insect, releasing nutrients that are absorbed by the leaf surface. Unlike the well known Venus Flytrap, Dionaea spp., Drosera does not snap its leaf shut on a captive, but its sticky tentacles slowly move to increase the amount of surface contact with its prey.In July and August the sundew blossoms, producing a raceme with up to fifteen white or pink flowers, all growing on one side. The stalk is leafless and can be 2" to 14" long. Each flower has 5 petals and 5 sepals.

Drosera have medicinal properties and are used today in hundreds of registered medications to treat respiratory ailments such as asthma. Native sundews are protected in nearly all countries in the world, so they must be raised commercially for the pharmaceutical industry. Drosera rotundifolia and D. intermedia are fast-growing members of the genus, and thus are two of several Drosera species commercially grown.

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Joe O'Rourke