Kevin Nixon

According to Wiegand & Eames (ref.1) there are seven species of Vaccinium growing in the Cayuga Lake Basin: V. stamineum (deer or huckleberry), V. corymbosum (high bush blueberry), V. angustifolium (low bush blueberry), V. pallidum (late upland blueberry), V. myrtilloides (velvet leafed blueberry), V. oxycoccus (small cranberry), and V. macrocarpon (large cranberry). I chose to write about Vaccinium because it is August and that is when I head out to local U-Picks to fill my freezer with the cultivated varieties of our native high bush blueberry. I had known that there were low bush blueberries and huckleberries growing locally, as I have seen them on hikes through the Lindsay Parsons biodiversity preserve and the Danby State Forest, but I was surprised to find out that cranberries grow in our area as well.

The blueberries, with the exception of V. corymbosum, tend to grow in dry or gravelly soils in open woods, from acid to non calcarious soils to slightly calcarious soils. The high bush blueberry grows in or near acid or calcareous bogs, whereas the cranberries grow in acid bogs or boggy acid soils. Interestingly, the cultivated high bush blueberries are mostly found on our hill tops, seemingly the antithesis of ‘in or near bogs’.

The fruits of all these plants are delicious to humans and the preferred foods of many species of birds, as well as raccoons, dogs, bears, fox, and coyotes. They also have a lovely fall color of scarlet red, and the bees certainly work hard pollinating them. They are worth planting in your landscape, and are pretty adaptable as long as they don’t have to go without moist soil. If you plant shrubs now, in just 3 to 5 years you should be able to get a sizable fruit crop, and in 10 to 20 years, you won’t have to pay for berries ever again!

There are many U-Pick farms in the area, all in pretty locations, most with nice views. Blueberries are high in antioxidants but really, are just a wonderful taste of summer.

References:

1. Karl M. Wiegand and Arthur J. Eames, The Flora of the Cayuga Lake Basin, New York, Ithaca, NY, May, 1928

About

By Sarah McNaull

Photos by Kevin Nixon

Plants Referenced

One of the most important trees for honey production, basswood flowers when the leaves are mature, usually in June here in the Finger Lakes. In flower, basswood is often found by listening to the buzz of bees collecting nectar from its blossoms. The fragrant yellow to white flowers grow in clusters and are subtended by a narrow, green, leaf-like blade.

Basswood fruits are 1/3" in diameter, globose, nutlike and have a hard outer shell with a small seed. The fruits remain attached well into winter, and are one of the easier ways to identify this tree. I had been walking past a filled in kettle hole for years when one winter I noticed the fruits of Tilia on the snow about 100' away which led me to find one of many large basswoods close to my home. Trees produce seeds starting at about 15 years and have been known to continue fruiting yearly for up to 85 years.Tila americana bark is a very dark brown with continuous, narrow ridges going up the tree. Young bark is smooth and grey, dark green or red (the ones I looked at this weekend were all red) with long lenticels. The twigs are zig-zagged and don't have a terminal bud. The lateral buds are .2 to .25" and have two visible red scales, which are lopsided and mucilaginous. Tilia bark (both the European and North American species) is the best woodland source for rope, string, thongs or strips for sewing birch bark. To get the fibers to make into rope, the bark is soaked in water for two to four weeks until the fibers separate.

Tilia wood is well known for its carving properties. It is also used in furniture making, though it is then covered with a veneer of other woods. Historically the wood was used for pulp in early paper production.

About

By Sarah McNaull

Photos by Kevin Nixon, Joe O'Rourke

Plants Referenced

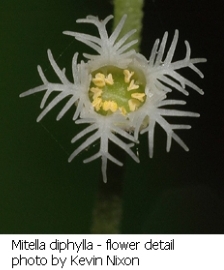

We have two Mitella species in the Finger Lakes region - Mitella diphylla and M. nuda (naked mitrewort). The easiest way to distinguish these three species is the flowering stalk. Unlike Tiarella or M. nuda, M. diphylla has two small, stalkless, opposite leaves on the flower stalk itself, above the level of the basal leaves. Naked mitrewort is smaller in every aspect (see below), less common, has rounder leaves, and blooms a bit later than M. diphylla or Tiarella cordifolia. Tiarella leaves are often wider than Mitella, and are more likely to have variegation.

Specifics from the CT Botanical Society web site and USDA Plants:M. diphylla - 8-18 inches high with white 1/8th inch flowers produced between April - May; distribution - eastern North America (Ontario to Quebec, south to Arkansas and Georgia).

M. nuda - 3-8 inches high with pale greenish white 1/16th inch flowers produced May-August in rich woods; distribution- northern North America (Washington to Pennsylvania north to Alaska, Nunavut, and Newfoundland).

Tiarella cordifolia - 6-12 inches high with white ¼ inch flowers produced between April - June; distribution - eastern North America (Ontario to Nova Scotia, south to Missouri and Georgia).

Cultivation: Mitella diphylla is easily grown in rich, moist soil in shade. The seed capsules split to leave small black seeds “sitting” in the cupped lower portion until they are spilled onto the soil. The seeds germinate readily after cold, moist stratification. All three species prefer somewhat acidic soil, but both M. diphylla and Tiarella cordifolia do well in my neutral - limey garden beds. Because M. nuda is much scarcer here, and because it seems to prefer cooler, wetter sites in our region, I have never tried to grow it.About

By Rosemarie Parker

Photos by Kevin Nixon, Paul Schmitt, K. Kohout, RP Kowal

Plants Referenced

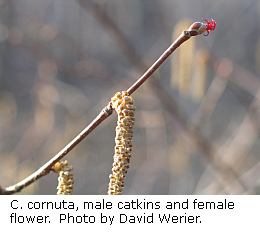

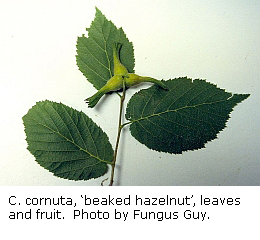

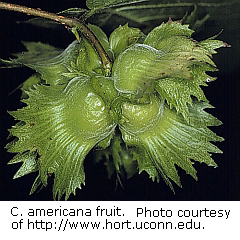

Corylus americana, American hazelnut, and C. cornuta, beaked hazelnut, are both native to the Finger Lakes. The prominent catkins are the male inflorescences; the female flowers are very inconspicuous until they open and reveal their scarlet styles. The female flowers become edible nuts by fall. If you can beat the squirrels to them, the nuts are said to be of similar quality to commercial filberts, just smaller. Their leaves, serrated and strongly veined, have lovely brown to yellow fall colors. In the Finger Lakes region, the European hazelnut, Corylus avellana, is recorded from Livingston county, and may have escaped elsewhere in this region, plus various Corylus cultivars are used in landscaping. But if you see a hazelnut in the woods or at the edge of a swamp, it is likely to be one of our natives.

American hazelnut fruit is easily distinguished from the beaked hazelnut. The bracts extend around the nut in both species, completely covering the nut in the beaked. Bracts extend roughly twice the length of the nut for C. americana, and are even longer in C. cornuta, extending into a tubular beak. Corylus americana is shrubby (3-5m), with smooth grey bark, and has more pubescent (to bristly) twigs than C. cornuta. Corylus cornuta is about the same size (4-6m), has smooth brownish bark, and has glabrous to sparsely pubescent twigs. Vegetative individuals of C. cornuta can be distinguished from C. americana by the absence of glandular hairs on the petioles and young twigs. (Flora NA). For additional descriptions and comparisons, see the links below.

The Tompkins County Flora (TCF 2008) at Cornell’s Bailey Hortorium has Corylus americana specimens from 1875 in Six Mile Creek and other locations in Tompkins county through the early 1900s. (Most were collected in early April or late March, possibly reflecting their most visible period.) In the Cayuga Lake basin, C. americana is currently listed as scarce (Wesley 2008). Present throughout the Finger Lakes and coastal counties of New York, C. americana is considered common statewide (NYFA). In fact, in some parts of its North American range (Eastern Canada & U.S. south through GA & LA), C. americana is apparently considered rather weedy. It is an upland species, growing in thickets, open woods, and disturbed areas. The earliest specimen of Corylus cornuta in the Tompkins County Flora was collected by Wiegand himself in 1892 from Cascadilla ravine (TCF 2008). Corylus cornuta is still common in the Cayuga watershed (Wesley 2008) and is found throughout the state (NYFA). It is an understory shrub in deciduous and mixed deciduous coniferous forests in west-central to eastern North America (Flora NA). Beaked hazelnut also occurs on forest edges, cut forests, and in thickets, generally in thin poor soils (NYFA).Twigs, bark, and nuts of both species have been used medicinally (Ethno).

References:

- TCF 2008: Tompkins County Flora Project

- Wesley 2008: Vascular Plant Species of the Cayuga Region of New York State; F. Robert Wesley, Sana Gardescu, and P. L. Marks © 2008;

- NYFA: 2009 New York Flora Atlas; Weldy, Troy and David Werier. [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (original application development), Florida Center for Community Design and Research. University of South Florida]. New York Flora Association, Albany, New York.

- Ethno: Native American Ethnobotany; (University of Michigan - Dearborn)

- Flora NA: Flora of North America

C. americana links:

- http://www.hort.uconn.edu/Plants/c/corame/corame1.html (concise info on landscape use)

- http://www.cnr.vt.edu/DENDRO/DENDROLOGY/SYLLABUS/factsheet.cfm?ID=208 (several images + concise info)

- http://www.rook.org/earl/bwca/nature/shrubs/corylusam.html (good description of habitat)

C. cornuta links:

- http://www.rook.org/earl/bwca/nature/shrubs/coryluscorn.html (good description of habitat)

- http://www.cnr.vt.edu/DENDRO/DENDROLOGY/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=144 (several images + concise info)

About

By Rosemarie Parker

Photos by David Werier, Kevin Nixon, Fungus Guy, UConn Plant Database

Plants Referenced

Spring Beauty, Claytonia virginica, is in the family Portulacaceae and was named for John Clayton (1686-1773) who was Clerk to the County Court of Gloucester County, Virginia from 1720 until his death. He has been described as the greatest American botanist of his day and was one of the earliest collectors of plant specimens in that state.

The name says it all. It is truly a beauty in spring with its pink-striped flowers. One plant doesn't make much of a splash, but it seeds itself in such profusion to create carpets of pink. Last spring in my yard it covered an area of 6-8 square feet. It is a delicate, fragile-looking beauty which belies its true nature. In prior years I have spotted the grass-like leaves of Spring Beauty in late January, but never as early as December 10th.

(In correspondence, John Gyer wrote, "Its growth starts again in September when soil temperatures are lower and soil moisture increases. It first produces an extensive root system, which nearly exhausts the energy reserves of the corm. The corm becomes rubbery as the energy reserves are used up. Leaves begin to appear after the energy reserves are half or more exhausted and the corm begins to recover turgor. The growth seems temperature and moisture dependent. Soil temperatures of less than 55F are needed for growth in a good moist soil. Temperatures below about 35F will slow or terminate growth, but do not seem needed to complete the growth cycle." John also reports growing a yellow-flowered form. )

By the end of March, it is all budded up waiting for a warm sunny day to open its flowers. From then into May it makes a delightful sight wherever it has chosen to grow. It is a small plant growing only three to six inches tall with both basal leaves and a pair of narrow leaves on the stem. The stem terminates in a raceme of small flowers, consisting of five petals that are white with fine pink stripes that vary in intensity. On cloudy days the stem droops and the flowers close only to open again on another sunny day. Sunny days bring out the pollinators - all sorts of bees and Claytonia virginica flies and occasional butterflies. The flowers when fertilized produce a capsule containing a few seeds. By the end of May it has formed and dispersed its seeds, stored up enough energy for the next year, decides it doesn't like hot weather and bids a fond adieu. Like other spring ephemerals - Dutchman’s’ Britches, Squirrel Corn and Virginia Bluebells, it takes advantage of the leafless trees in spring to complete its above ground growth. As with spring bulbs one must be careful when digging around them.

Another common name is Fairy Spuds, derived from the small spud-like edible corm. Fernald and Kinsey in their "Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America" state that when boiled in salted water are palatable and nutritious, having the flavor of chestnuts. They further state that the succulent Claytonia virginica young plants are a possible potherb. The Algonquins ate the cooked corms like potatoes. I have not tried it, but maybe I will this spring. The Iroquois used a cold infusion of the roots as an anticonvulsive for children. The raw plants were also used as a contraceptive.

It has quite a wide distribution, occurring from Massachusetts west to Nebraska, south to Georgia and extending into Texas. The New York Flora Association lists it as native to Chemung and Tompkins counties, but lists no reports from Steuben or Schuyler counties. It is found in a number of habitats, but moist woods with dappled sunlight are a favorite habitat. One source stated that it will adapt to semi-shaded lawns if mowing is delayed. Another neat thing to try. Since it starts its growth early, I surmise that deer might be a problem in early spring. The fact that it is such a low-growing plant should work to its advantage. Voles and other small rodents are reputed to occasionally eat the corms. [Ed. note: Neither deer nor chipmunks & squirrels have touched the spring beauty in my lawn as it has spread during 12 years.]About

By Bill Plummer

Photos by Kevin Nixon

Plants Referenced

When the sunny spots in our woods are carpeted by the nodding yellow flowers of the trout-lily, Erythronium americanum, it is a sure sign that spring has arrived in central New York.

As its name suggests, these lovely spring wildflowers are members of the lily family, Liliaceae. They like rich woods and are typically found growing in extensive colonies consisting of hundreds of plants. Most plants will be flowerless, but the leaves themselves are attractive, having reddish-purple and lighter green blotches against a dark green background.

The plant can reproduce by seed, but it favors vegetative propagation. Each plant forms a corm, an underground tuber-like structure that stores food to help the plant survive the winter. The plants send out runners in the spring, which produce a new plant at the end. Young plants have single small leaves. They produce at least two leaves when they are big enough to flower, which can take up to seven years. One author mentions a study of trout-lily in which "the colonies were found to average nearly 150 years in age and were as old as 1,300 years." (ref 1)

The plants are small, generally two to ten inches in height. In rich soils, you tend to find fewer and larger plants. In poorer soils, you tend to find more and smaller plants. The flower is large in comparison to the plant, being an inch or so in width. It has three reflexed sepals and three reflexed petals. The backs of the sepals may have a reddish-purple tinge.

Erythronium americanum goes by many names. It is called "adder's tongue" probably because its leaf resembles that of a tiny fern called adder's tongue, Ophioglossum vulgatum. Another common name is "dogtooth violet". The plants, but especially the leaves, resemble the European species of Erythronium, which is Erythronium dens-canis. The European species has flowers that are pink-purple colored and so it is called "dogtooth violet" even though it is not a violet, botanically. "Dogtooth," I think, refers to the appearance of the corm. The naturalist, John Burroughs, coined the term "Trout-lily," probably for the speckles or blotches on the leaves that resemble the markings of many kinds of trout.There is a related species with white flowers, Erythronium albidum, which is found west of our area in the midland states. There are several records of it scattered throughout upstate New York including the nearby Chenango County (ref 2). It does not occur in the Ithaca area. It is found in Western New York, but it is uncommon (ref 4). Weigand and Eames do not list the white species at all (ref 3).

Reference:

1)Shelter, Stanwyn G., Yellow Trout-lily - A Lily of Many Aliases

2) Personal communication with Anna Stalter, Bailey Hortorium, Ithaca, NY.

3) Wiegand, Karl M. and Eames, Arthur J., "The Flora of the Cayuga Lake Basin, New York"; Cornell University, Ithaca NY; July, 1925

4) The New York Flora Atlas

About

By Joe O'Rourke

Photos by Kevin Nixon